When you think “archaeology” do you think “U.S. Army Corps of Engineers?”

Probably not. Archaeology brings up images of Indiana Jones, dusty tombs and getting chased out of caverns by giant rolling boulders. Yet, despite this, USACE curates the second largest collection of cultural resources in the United States, second only to the Smithsonian Institution.

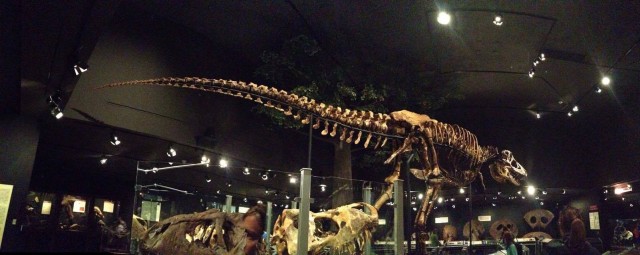

We even own a full Tyrannosaurus Rex skeleton.

Montana's T. rex is curated into the Museum of the Rockies National Paleontological Repository, on long-term loan from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The 40-foot-long skeleton is mounted on a steel frame that allows each individual bone to be removed for study. The science presented in this new exhibit was accomplished and published in scientific journals by the students, staff and faculty here at Montana State University, a tremendous benefit of placing these finds in the federal repository. (This photo is a panoramic - composed in camera with a smartphone)

Sure – we’ve loaned it out to the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of Natural History for half a century, but facts are facts, that big mean fossil is ours.

So how did USACE become this powerhouse of archaeology and natural history? According to Little Rock District Archaeologist, Allen Wilson, it didn’t start in a tomb, or being chased by boulders while dodging arrow traps.

“Although archaeology is an exciting field, it’s not like what you see in the movies. In fact, Indiana Jones is a terrible archaeologist,” said Wilson.

In truth, USACE’s relationship with cultural artifacts and archaeology stem from the work they do in support of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. Section 106 states that the federal government must consider historic properties during any undertaking that takes place on federal lands, uses federal funds, or requires federal permissions.

Additionally, being a land management agency, USACE is subject to environmental laws such as the National Environment Policy Act and the National Historic Preservation Act. Upon full implementation of these laws in the early 1970s, USACE had to employ their own environmental staff, including archaeologists to keep up with the infrastructure needs of the nation. Passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972 expanded the scope of USACE’s duties and authorities under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.

So, for example let’s say construction starts on a project on federal land – or in an area designated as a wetland and requires a regulatory permit. One of the many things that must happen before work can start is a Cultural Resources Survey.

A Phase I survey involves digging holes in grid pattern on the landscape and screening the contents for artifacts. If artifacts are found, they are recorded and USACE must determine if it is eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

According to Wilson, any site found is considered eligible, until proven otherwise. Eligibility is usually determined by a Phase II testing of the site. Phase II involves excavation in a scientific grid and in closely measured levels to identify features and artifacts in the site and determine whether it meets the criteria to be on the NRHP.

If a site is located and determined to be eligible, and if that site cannot be avoided by the proposed undertaking, USACE must then enter into an agreement with the state and any cultural or tribal organizations with an interest in the area. The intent is to mitigate any damage to the site while learning as much as possible. Once an agreement is reached, archaeologists get to work.

“If the site cannot be avoided, it usually requires a Phase III data collection,” says Wilson. “We gather as much information about the portion of the site, or the entire site as we can.

During this survey, they work to uncover as much as possible including various historic and prehistoric objects. According to Wilson, this includes objects that people have used or modified and that are over fifty years old. Historic artifacts can include ceramics, glass, buildings/ foundations, cemeteries, trash piles, tools, mill runs and building materials. Prehistoric items can include ceramics, stone tools, stone flakes, bannerstones, organic materials (fabric/cordage) from rock shelter or cave sites, grinding stones, and shell middens.

Once a site has been located, a determination must be made to see if the site is eligible to be included in the NRHP. A site, by virtue of just being fifty years old, does not mean it is eligible.

Eligibility is determined by applying four criteria:

1. The property must be associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history.

2. The property must be associated with the lives of persons significant in our past.

3. The property must embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, represent the work of a master, possess high artistic values, or represent a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction.

4. The property must show, or may be likely to yield, information important to history or prehistory.

It’s a lot of hard and exacting work that must take place, and it can impact a project’s timelines or may require an undertaking to be moved or altered in some way that doesn’t impact the site.

It’s important work, but little known, and not well understood by many. It’s also a job that touches many different parts of USACE. Any undertakings that occur on USACE land is delegated to the Operations Division, those that utilize USACE funding on projects outside of USACE land fall to the Planning Division, and those that require USACE permissions (regulatory permits) are handled by the Regulatory Division; with the laws and standards governing them being the same for each division.

Yet surveys on project sites aren’t the only place you’ll find archaeologists like Wilson working.

One of the most common places you’ll find them are at USACE project offices, working hand in hand with rangers and natural resource specialists to preserve artifacts found by campers, hikers and hunters.

“USACE parks and lakes draw a lot of people, including amateur archaeologists and treasure hunters,” Wilson said. “Yet taking artifacts or starting your own excavation on federal land is very illegal and comes with severe penalties.”

According to Wilson, the Archaeological Resources Protection Act enacted in 1979 protects artifacts found on federal property and can levee heavy fines or even jail time for those that disturb or remove artifacts.

While archaeological fieldwork can happen on federal lands, ARPA strengthens the permitting procedures required for conducting that fieldwork.

Currently, there are numerous ongoing archaeological sites in the Little Rock District. One that is listed on the NRHP, is the resort town of Monte Ne located in Rogers, AR. Monte Ne was founded in 1900 by William H. “Coin” Harvey. It had the world's largest log hotels, designed by architect A. O. Clark, and attracted visitors from across the country for more than two decades.

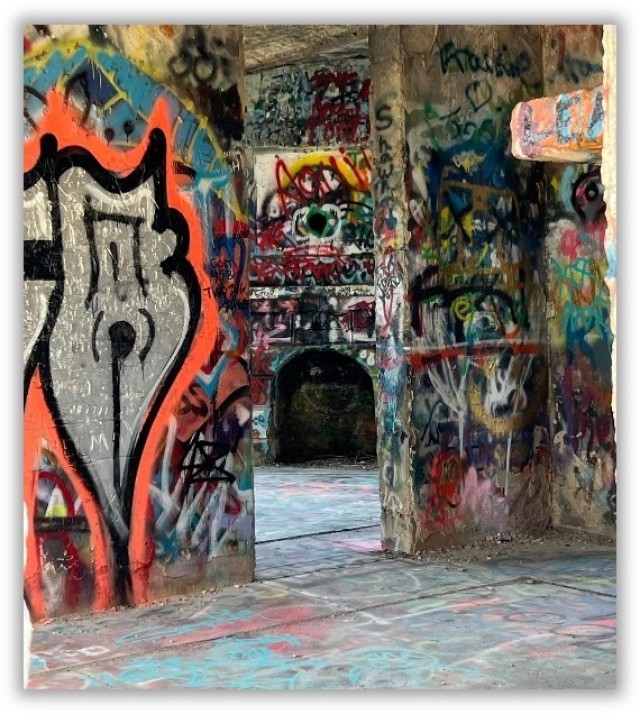

The Oklahoma Row Site at the former Monte Ne Resort, a three-story concrete tower listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The property became USACE’s after the White River was dammed to create Beaver Lake in the mid-1960s, leaving much of the resort and original town of Monte Ne under water.

The foundation and tower of Oklahoma Row, the amphitheater, a fireplace, chimney, foundation, and a retaining wall from Missouri Row are all that is left.

The Oklahoma Row tower has become a lure for illicit and often dangerous activities as well as numerous acts of vandalism despite the site being on the National Register of Historic Places and USACE taking measures to restrict access for safety.

The Oklahoma Row Site, a three-story concrete tower, is listed on the NRHP.

It is important that historical sites are preserved because there are very few protections afforded to these resources outside of those located on federal lands.

USACE balances the needs of our continually growing nation by preserving an area if possible, and documenting it and studying it extensively if not, to ensure that the historical legacy of those who came before us is not lost, prior to altering a landscape.